When researchers evaluate a prediction market, they need to answer a simple question: at what moment do you read the price? The answer determines your Brier scores, your calibration curves, and your conclusions about which platform forecasts better. Despite this, the question is almost never asked explicitly. It is treated as a detail—something settled by convention or convenience rather than by argument.

That was fine when prediction markets resolved quickly. It is less innocuous now. On modern platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi, the gap between when an event outcome becomes known and when a contract formally resolves can span hours or days. During that gap, trading continues. Prices during this window do not reflect forecasts. They reflect the mechanical convergence of a market that already knows the answer.

Using those prices as a measure of forecast quality implicitly assumes that settlement timing is irrelevant—an assumption that was previously innocuous but now matters. As far as we can tell, most current applied work on these platforms relies on resolution-relative prices without examining this assumption.

Two truncation regimes

There are two ways to decide when to sample a prediction market price for evaluation:

- Event-time truncation: Sample the price relative to when the real-world event occurs (e.g., election day). The price reflects what the market believed before the outcome was known.

- Resolution-time truncation: Sample the price relative to when the platform formally settles the contract. The price may include post-outcome trading if there is a lag between the event and resolution.

On the Iowa Electronic Markets, these two regimes were effectively identical. IEM contracts resolved almost immediately after elections. There was no meaningful gap to worry about, and so the distinction never needed to be articulated.

On Polymarket and Kalshi, they are not identical. Polymarket's documentation states that markets settle "within 24 to 48 hours after the event outcome becomes definitively known." Kalshi's automated settlement typically runs within 3 to 12 hours. For some contracts, the lag is longer—waiting on official certifications, court rulings, or manual review.

This means "1 day before resolution" is not the same as "1 day before the event." The offset varies by platform, by contract, and sometimes by the idiosyncrasies of how a particular outcome was confirmed. If you compare Polymarket and Kalshi using resolution-relative timestamps, you are not comparing their forecasts at the same moment. You are comparing prices contaminated by different amounts of post-outcome information.

What the literature actually does

We reviewed how truncation is handled across studies that evaluate forecast accuracy or calibration in political prediction markets, from the classic IEM research through the most recent work on Polymarket and Kalshi. Our focus is on studies that use market prices to assess predictive performance, rather than on work examining trading behavior or price discovery. The pattern is clear.

| Study / Domain | Price used | Truncation rule | Explicit discussion? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berg, Nelson & Rietz (2008), IEM studies | Last price near event | Event-time (implicit) | No |

| Wolfers & Zitzewitz (2004, 2006) | Prices at fixed horizons | Event-time, multi-horizon | Yes (implicit) |

| Erikson & Wlezien (2012) | Daily probabilities up to Election Day | Event-time | No |

| Dudík et al. (2017) | Not focused on evaluation | Theoretical convergence | No |

| Clinton & Huang (2025) | Last price before resolution | Resolution-time | No |

| Cutting et al. (2025) | Daily closing prices to Election Day | Event-time (incidental) | No |

| Brüggi & Whelan (2025) | Final settlement price | Resolution-time | No |

| Chen et al. (2024) | Full trading history | N/A (behavioral study) | No |

The classic literature—Berg, Wolfers, Erikson—uses event-time truncation. It does so implicitly, because on IEM-era markets the distinction was moot. The treatment is coherent even though it is not formally justified: once the event happens, the market has no informational role. This was taken as obvious.

Among recent work that explicitly evaluates calibration or forecast accuracy, there has been a gradual shift toward resolution-relative timing, often driven by data availability and platform design rather than by explicit methodological commitments. Clinton and Huang (2025), the most comprehensive cross-platform study to date, use the final closing price before market resolution as the forecast—a natural choice given the data, but one that does not distinguish whether the outcome was already known before the market resolved. Brüggi and Whelan (2025) use final settlement prices to study calibration on Kalshi, which can conflate belief aggregation with mechanical convergence.

The issue arises less from the authors' stated goals than from how these results enter broader comparisons. The cumulative effect is that the field has shifted truncation regimes—largely without discussion—and the shift can introduce systematic bias into accuracy comparisons.

Why this is not a nit

Resolution time is an institutional property of a platform. It reflects settlement procedures, verification protocols, and sometimes just how quickly someone updates a webpage. It has nothing to do with how well the market aggregated information before the outcome was known.

Post-event trading reflects certainty, not beliefs. Once election results are reported, prediction market prices converge toward 0 or 1. This is not forecasting. It is mechanical. Including this convergence in your accuracy metric biases Brier scores downward—making markets look more accurate than they actually were as forecasters.

The bias is not uniform across platforms. Polymarket's longer settlement window means more post-outcome trading is included when you truncate relative to resolution. Kalshi's faster settlement means less. In a head-to-head comparison using resolution-relative prices, this asymmetry can mechanically advantage platforms with longer settlement windows, holding forecast quality fixed—because more of the measured "forecast" consists of already knowing the answer.

Consider a hypothetical case that illustrates how truncation timing alone can alter measured accuracy. Polymarket prices a Senate race winner at 0.72 on election eve. Kalshi prices the same winner at 0.68. The winner wins. Using election eve prices, Polymarket's Brier score is 0.0784, Kalshi's is 0.1024. Polymarket was more confident and more accurate.

Now use "1 day before resolution." Polymarket settles 36 hours after results are called; 1 day before resolution, the outcome is known, the price is 0.95. Kalshi settles 8 hours later; 1 day before resolution, results were just being called, the price is 0.85. Polymarket's Brier score drops to 0.0025. Kalshi's drops to 0.0225. Both appear more accurate than they were as forecasters, and the relative gap between them has changed—not because of anything about forecast quality, but because of settlement timing.

This pattern is inherent to any analysis that uses resolution-relative timestamps on platforms with different settlement procedures. Results are sensitive to the truncation choice, even when forecast quality is held constant.

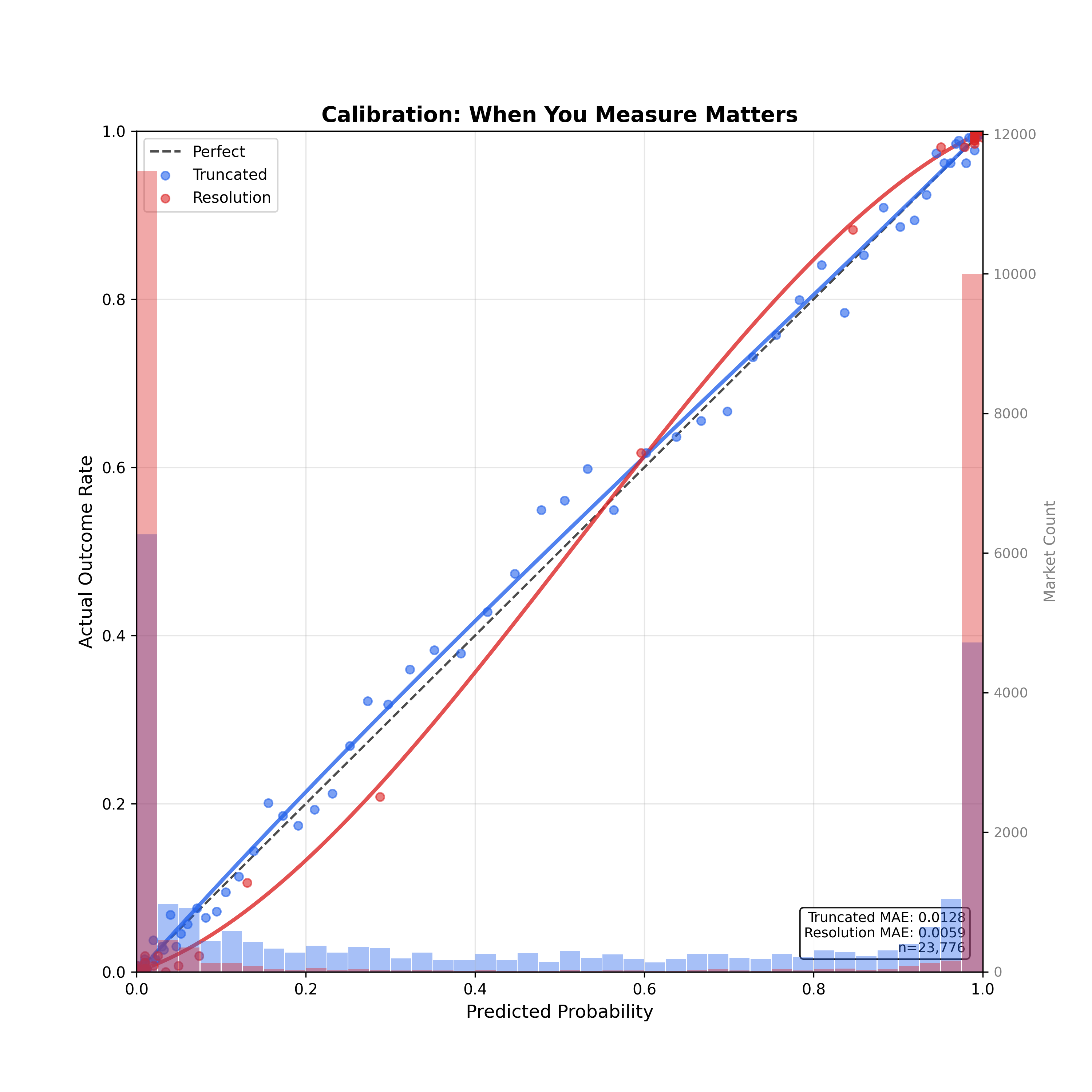

Figure 1 shows this empirically. Using 23,776 resolved political markets from Polymarket and Kalshi, we compare calibration curves for the same markets measured two ways: truncated prices (sampled before outcomes are known) versus resolution prices (the true last traded price before settlement). For electoral markets, we use the election eve price—00:00 UTC on election day, before any polls close. For non-electoral markets—policy announcements, court decisions, economic releases—we truncate relative to trading close with platform-specific offsets that account for each platform's typical settlement lag. The resolution prices appear dramatically better calibrated—a mean absolute error of 0.006 versus 0.013—but this is largely mechanical. The background distributions tell the story: resolution prices pile up at the extremes (0 and 1) because by that point, outcomes are known and prices have converged. Truncated prices show the actual distribution of market beliefs before resolution.

What almost no research does

Based on the available literature, no academic study of Polymarket or Kalshi:

- Formally distinguishes event knowledge time from market resolution time

- Compares alternative truncation rules head-to-head

- Treats truncation as a design choice subject to bias analysis

- Explicitly accounts for post-event trading or information leakage before resolution

- Tests how much the truncation choice changes reported accuracy metrics

This represents an opportunity for greater methodological transparency. The distinction between when an outcome is known and when it is formally resolved is precisely the kind of design choice that can affect conclusions in cross-platform comparisons, shift calibration assessments, and influence which platform appears more accurate in a given benchmark.

Dudík et al. (2017) provide the theoretical framework for thinking about this—their decomposition of forecast error into sampling, convergence, and market-maker components maps directly onto the truncation problem. But their framework was built before the resolution lag issue existed in practice, and it does not prescribe an evaluation protocol for markets where trading continues after the outcome is public.

Our approach

Our goal is not to prescribe a single correct truncation rule, but to make the timing choice explicit and to show how it affects interpretation. For electoral markets in the Bellwether dataset, we use a fixed rule: the market price at 00:00 UTC on election day. For U.S. elections on November 5, this corresponds to approximately 7:00–8:00 PM Eastern on November 4—the evening before any polls close. For elections in other time zones, the local time varies, but the UTC timestamp is universal and unambiguous.

We call this the election eve price. Here is why.

It is event-anchored, not resolution-anchored. The same election yields the same measurement timestamp on Polymarket and Kalshi. Cross-platform comparisons become comparisons of forecast quality at the same moment, not artifacts of settlement procedure.

It is pre-outcome. At UTC midnight on election day, no U.S. election results have been reported. No polls have closed anywhere in the country. The price reflects the market's assessment of what will happen, not a reaction to what has. This is what "forecast accuracy" should measure.

It is reproducible. UTC midnight is a universal standard. No time zone ambiguity, no daylight saving adjustments, no platform-specific offsets. Any researcher can replicate the measurement with the same timestamp arithmetic. Cutting et al. (2025), comparing Polymarket to polling, note the implicit difficulty of aligning daily market probabilities with poll data—a problem that stems from unstandardized timing. A fixed UTC anchor avoids it.

It is the natural "final forecast" moment. The evening before an election is when voters, campaigns, and media make final assessments. Wolfers and Zitzewitz (2004, 2006) treat forecasts as time-indexed objects and evaluate accuracy conditional on the horizon. Election eve is the shortest reasonable horizon at which the market is still pricing genuine uncertainty.

Limitations

UTC midnight is somewhat arbitrary. One could argue for 6 hours before polls open, or the moment of the last pre-election poll. For non-U.S. elections where voting begins at different local times, the gap between UTC midnight and the first returns varies. And for non-electoral markets—policy announcements, court decisions, economic data releases—there is no natural "election day" to anchor to. For these contracts, we truncate relative to each platform's trading close time, subtracting the typical settlement lag: 24 hours for Polymarket (which typically closes trading a day after the event) and 12 hours for Kalshi (which settles faster). This aims to capture the final prediction price before the outcome becomes known, though the exact timing varies by contract type.

More fundamentally, no single truncation point captures everything. Early prices reflect thin liquidity and wide uncertainty. Late prices reflect near-certainty or post-event convergence. The "true forecast" is a property of the entire price path, not a single reading. Dalen (2025) proposes a continuous-time stochastic model that could in principle identify optimal sampling windows, but in practice that requires estimating latent parameters that are themselves sensitive to modeling assumptions.

For applied work, a fixed, transparent rule is more practical and more reproducible than a theoretically optimal one. Our aim is to make this design choice visible—to use a truncation point that is defensible, consistent across platforms, and grounded in what we are actually trying to measure: what the market believed before the answer was known. Rather than overturning prior conclusions, we hope this adds a dimension of transparency and comparability to an active and growing literature.

References

- Berg, J., Nelson, F., and Rietz, T. "Prediction Market Accuracy in the Long Run." International Journal of Forecasting, 2008.

- Wolfers, J. and Zitzewitz, E. "Prediction Markets." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2004.

- Wolfers, J. and Zitzewitz, E. "Interpreting Prediction Market Prices as Probabilities." NBER Working Paper, 2006.

- Erikson, R. and Wlezien, C. The Timeline of Presidential Elections: How Campaigns Do (and Do Not) Matter. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Dudík, M., Lahaie, S., Rogers, R., and Vaughan, J. "A Decomposition of Forecast Error in Prediction Markets." arXiv preprint, 2017.

- Clinton, J. and Huang, T. "Prediction Markets? The Accuracy and Efficiency of $2.4 Billion in the 2024 Presidential Election." SocArXiv preprint, 2025.

- Cutting, D., Hughes-Berheim, R., Johnson, M. et al. "Are Betting Markets Better than Polling in Predicting Political Elections?" arXiv preprint, 2025.

- Brüggi, F. and Whelan, K. "The Economics of the Kalshi Prediction Market." UCD working paper, 2025.

- Sethi, R. "Political Prediction and the Wisdom of Crowds." Communications of the ACM, 2025.

- Chen, Y., Duan, J., El Saddik, A., and Cai, W. "Political Leanings in Web3 Betting: Decoding the Interplay of Political and Profitable Motives." arXiv preprint, 2024.

- Dalen, A. "Toward Black-Scholes for Prediction Markets: A Unified Kernel and Market Maker's Handbook." arXiv preprint, 2025.